Listen to the Podcast

4 October 2024 - Podcast #902 - (17:41)

It's Like NPR on the Web

If you find the information TechByter Worldwide provides useful or interesting, please consider a contribution.

If you find the information TechByter Worldwide provides useful or interesting, please consider a contribution.

When you direct your browser to a website, the website asks questions before displaying anything. Some of the information requested is essential for the site to display properly, but additional questions may also be asked and these allow commercial sites to track you around the internet.

Imagine an old department store with different areas operated by various business owners. The men’s apparel area has a list of customers, as does the women’s apparel area, the bookstore, the toys section, and the home furnishing department. Because it’s a department store, the merchants probably all share their customer lists. Then the department store acquires a computer and can keep track of which people buy what items. Eventually, the store could track you from department to department and learn what you’re interested in.

That’s exactly what the internet allows merchants to do, but on a grand scale — far beyond anything individual merchants ever considered.

So websites ask a lot of questions. They want to know what browser you’re using, what the computer’s screen size is, what the browser’s window size is, your IP address, which typefaces are available, whether you’re running an ad blocker, what types of video and audio files the browser can accept, where you are, and more.

Many browsers respond to the “What browser are you?” question with this response: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/129.0.0.0 Safari/537.36 Edg/129.0.0.0 because most current browsers have few differences in how they interpret HTML and CSS code. Screen size is more important. The presence of an ad blocker will be important for those who operate sites that are funded by ads. Your location could be important for restaurants and delivery services. In other words, the site has logical and ethical reasons for asking some questions.

But some sites include code from other sites. There are reasonable and ethical reasons for doing this. The TechByter Worldwide site loads some cascading stylesheet code and typefaces from external sources such as JQuery. There are links to PayPal, Facebook, StatCounter, Sitelock, W3 Organization, StatCounter, CloudFlare, and Site24/7. None of these does any tracking.

Some web pages include content from external domains and may use cookies and other methods to track your browsing habits — often to display advertisements. The domains that do this are called “third party trackers”.

Do Not Track and Global Privacy Control settings already exist and setting these in your browser’s configuration settings would keep sites from tracking you if they responded honestly and accurately. Few do. Regardless of those settings, sites that want to track you will track you.

You might be surprised by the amount of information that can be coaxed from your browser. It’s important to understand that none of this information is personally identifiable. The most it can do is identify your browser with high reliability.

Click any small image for a full-size view. To dismiss the larger image, press ESC or tap outside the image.

Visit Device Info and you’ll see information about your computer’s operating system, the browser, the computer’s public IP address unless you’re using a VPN, possibly the browser’s location, what time zone you’re in, microphone and speaker information, camera permissions, Bluetooth support, installed fonts, browser plugins, screen resolution, and more.

Visit Device Info and you’ll see information about your computer’s operating system, the browser, the computer’s public IP address unless you’re using a VPN, possibly the browser’s location, what time zone you’re in, microphone and speaker information, camera permissions, Bluetooth support, installed fonts, browser plugins, screen resolution, and more.

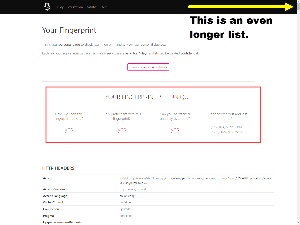

Another site to visit is the Browser Fingerprint Study site. This is a project by security and privacy researchers at Friedrich-Alexander University in Germany. It’s been in operation since 2016 and you can create an account that lets you track your browser’s ability to be identified over time. You’ll receive an email reminder once a week to check the browser. Signing up is optional and you can check the browser’s fingerprint whenever you want whether you sign up or not.

Another site to visit is the Browser Fingerprint Study site. This is a project by security and privacy researchers at Friedrich-Alexander University in Germany. It’s been in operation since 2016 and you can create an account that lets you track your browser’s ability to be identified over time. You’ll receive an email reminder once a week to check the browser. Signing up is optional and you can check the browser’s fingerprint whenever you want whether you sign up or not.

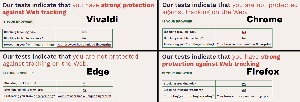

And swing by the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Cover Your Tracks site. This is a good site to visit with each of your browsers because you’ll see that built-in protection against tracking varies.

And swing by the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Cover Your Tracks site. This is a good site to visit with each of your browsers because you’ll see that built-in protection against tracking varies.

Beyond that, this site shows the most commonly used metrics that are combined to establish a browser’s unique fingerprint. I found that Vivaldi’s user agent information is common. About 1 in 21 browsers will report the value. Screen size and color depth are also common, 1 in about 30 browsers. But further down we see hashes of the canvas fingerprint and the WebGL fingerprint, 1 in 32,500 browsers and 1 in 39,000 browsers. When these specifications are considered in aggregate form, it’s trivial to exactly identify a specific browser.

Beyond that, this site shows the most commonly used metrics that are combined to establish a browser’s unique fingerprint. I found that Vivaldi’s user agent information is common. About 1 in 21 browsers will report the value. Screen size and color depth are also common, 1 in about 30 browsers. But further down we see hashes of the canvas fingerprint and the WebGL fingerprint, 1 in 32,500 browsers and 1 in 39,000 browsers. When these specifications are considered in aggregate form, it’s trivial to exactly identify a specific browser.

It would seem at least to be theoretically possible for an organization that has uniquely identified your browser to link that browser to you if you subscribe to something, buy something, request more information, or perform any other action that gives the site operator your name, address, and other information.

If you’d prefer not to have people you don’t know track you from site to site all over the internet, you can pay for utilities such as Avast AntiTrack for $55 per year ($65 for up to 10 Apple and Windows devices) or Norton AntiTrack for $50 per year ($35 for the first year).

Each of these defeats fingerprinting by lying. They inject false information into the data stream. That’s a procedure I don’t like and having to pay someone to have my browser lie is even less appealing. I like the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Privacy Badger, a free browser extension for Firefox and Chrome-based browsers.

Instead of lying to sites that ask inappropriate questions, Privacy Badger knows which sites aren’t trustworthy and, if a site isn’t on the good list or the bad list, it makes decisions based on the site’s behavior. It looks for tracking techniques like uniquely identifying cookies, local storage of supercookies, and canvas fingerprinting. If it observes a single third-party host tracking you on three separate sites, Privacy Badger will automatically disallow content from that third-party tracker.

The EFF explains Privacy Badger’s operation this way: Privacy Badger is an algorithmic tracker blocker – we define what “tracking” looks like, and then Privacy Badger blocks or restricts domains that it observes tracking in the wild. What is and isn’t considered a tracker is entirely based on how a specific domain acts, not on human judgment.

Privacy Badger shouldn’t be confused with ad blockers. Although it may block some ads, that occurs as a result of actions to stop trackers. It focuses on disallowing visible or invisible third-party scripts or images that appear to be tracking you even though you specifically denied consent by sending Do Not Track and Global Privacy Control signals. Most of these-third party trackers are advertisements. When you see an ad, the ad sees you, and can track you. Privacy Badger stops that.

To download Privacy Badger, use the Electronic Frontier Foundation page of Google Play store for Chrome-based browsers and download the extension from the EFF for Firefox.

When it comes to protecting users, Facebook always seems to be several miles behind the scammers. Because I want friends to be able to share any of my posts that they like, I make posts public. The downside to that policy is that the posts tend to attract barnacles.

I posted a photo in mid September and it had a like within seconds from a phony account that claimed to be Juliana Windell. She is from Amsterdam, her profile says, and she now lives in Knoxville. She also says “I believe in God and his timing,” whatever that is supposed to mean.

Click any small image for a full-size view. To dismiss the larger image, press ESC or tap outside the image.

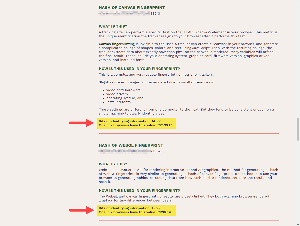

The banner picture appears to be AI generated and the profile picture definitely is unless “Juliana Windell” has a 16-inch waist and 48-inch hips. The photos depict someone who is substantially more clothed than is common for these fake accounts and the use of AI-generated images is relatively new. Previously scammers simply stole images of actual people from wherever they could find them.

The banner picture appears to be AI generated and the profile picture definitely is unless “Juliana Windell” has a 16-inch waist and 48-inch hips. The photos depict someone who is substantially more clothed than is common for these fake accounts and the use of AI-generated images is relatively new. Previously scammers simply stole images of actual people from wherever they could find them.

The fake account didn’t immediately ask me to send it a friend request, but that probably would have followed eventually. So far the scammer has one friend and, based on a quick examination of his account, he seems to be the gullible type.

My response? I clicked the dots and reported the fake account as a “Scam, fraud, or impersonation.” I selected the “financial or identity scam” option, but that’s based solely on a guess. The pretty ladies (who may be named Boris and live in a suburb of Moscow) usually entice their new friends and then find some reason to ask for money. Someone could develop a long con by asking for small amounts and quickly repaying them and then build up to a request for a substantial amount, after which “she” would disappear with the mark’s money.

My response? I clicked the dots and reported the fake account as a “Scam, fraud, or impersonation.” I selected the “financial or identity scam” option, but that’s based solely on a guess. The pretty ladies (who may be named Boris and live in a suburb of Moscow) usually entice their new friends and then find some reason to ask for money. Someone could develop a long con by asking for small amounts and quickly repaying them and then build up to a request for a substantial amount, after which “she” would disappear with the mark’s money.

After reporting the account, I blocked it.

This is a widespread problem on Facebook and it almost seems like Facebook doesn’t want to fix it. That or there are no competent programmers working there. These accounts are created and run by bots until they attract enough fools and I’d like to think that Facebook could institute closer monitoring of new accounts.

Until Facebook determines that it’s worthwhile to take out the trash, users will have to do it for them. It’s up to us to identify fake accounts, report them, and block them.

Users with no profile picture or pictures of semi-clothed people are immediately suspect. Women will be presented photos of men and men will see pictures of women. The names are often obviously fake. AI images so far are almost always identifiable as such. Brand new accounts with zero or few friends should be treated with caution. If the account has few or no posts, there’s a higher likelihood of fraud.

When you identify posts that have received likes from fake accounts, delete the likes by reporting the fake account and blocking it. Facebook rarely responds to these reports, so it’s hard to tell if someone or some algorithm actually takes action.

It’s far more frustrating and time consuming than it should be, but these actions are essential for our own security and that of our friends.

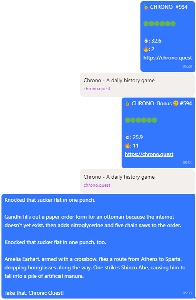

I’ve been playing Chrono Quest for more than two years, usually about 5:30 in the morning and every day it reminds me of a really bad history class, one that concentrates solely on dates.

Click any small image for a full-size view. To dismiss the larger image, press ESC or tap outside the image.

There’s a main game and a bonus game that’s offered if you win the main game. Winning involves placing six historical events in the correct chronological order in three or fewer tries. I solve about 60% in two tries, 28% in one try, and 12% in three tries. Occasionally I fail the main game. I get the bonus game in two tries about 55% of the time, in a single try around 33% of the time, and in three tries about 12% of the time.

There’s a main game and a bonus game that’s offered if you win the main game. Winning involves placing six historical events in the correct chronological order in three or fewer tries. I solve about 60% in two tries, 28% in one try, and 12% in three tries. Occasionally I fail the main game. I get the bonus game in two tries about 55% of the time, in a single try around 33% of the time, and in three tries about 12% of the time.

So I enjoy the game, but it certainly doesn’t teach anything about history.

Sometimes four of the six events occurred in a span of 20 years in the 1800s. Those are difficult, but it’s even worse when three or four of the events occur in a clump before the 1400s. One game started with all the events in the right order and, after looking at it for a while, I just clicked the Check Answers button.

A friend and I share our results each day, along with unlikely summaries of the events depicted. His strategy involves taking the time to think about the relationships of the events. My approach involves just slapping the six events into an order that seems plausible and checking the results. We have similar win ratios and sometimes write weirdly similar summaries.

If I get four of the six right on the first try, winning on the second go is guaranteed and, when I get three of the six right, it’s statistically impossible to lose, although I have managed to do it. The real challenges involve getting zero or one right on the first try.

If I get four of the six right on the first try, winning on the second go is guaranteed and, when I get three of the six right, it’s statistically impossible to lose, although I have managed to do it. The real challenges involve getting zero or one right on the first try.

Play Chrono Quest and you may find it amusing and sometimes frustrating, but never educational because learning just the dates eliminates contextual information. Understanding why something happened is far more important, along with who was involved and what the consequences were.

Simply memorizing dates discourages critical thinking. True historical knowledge requires analyzing sources, evaluating perspectives, and understanding motivations behind historical actions. Chrono Quest does nothing to link history to current problems. And concentrating on dates eliminates the struggles, achievements, and experiences of those who lived the events.

Knowing what else was happening in 1938 is more important than learning Superman comics were first published then. Or knowing where titanium comes from, how it’s used, and why it’s important is more useful than just knowing it was discovered in 1791.

Chrono Quest can be fun. Just don’t expect to learn anything by playing it.

TechByter Worldwide is no longer in production, but TechByter Notes is a series of brief, occasional, unscheduled, technology notes published via Substack. All TechByter Worldwide subscribers have been transferred to TechByter Notes. If you’re new here and you’d like to view the new service or subscribe to it, you can do that here: TechByter Notes.