Listen to the Podcast

13 September 2024 - Podcast #899 - (19:26)

It's Like NPR on the Web

If you find the information TechByter Worldwide provides useful or interesting, please consider a contribution.

If you find the information TechByter Worldwide provides useful or interesting, please consider a contribution.

I’ve titled this section with an absurd question. It’s absurd because it implies that an answer exists, but it doesn’t. At least not if you’re expecting a single answer.

Finding “the best” browser isn’t like solving a math problem. Multiplying 35 by 3 will always be 105. The square root of 625 will always be 25. Even those silly math puzzles that roil the internet because people don’t recall how PEMDAS (or BODMAS) works have correct answers, that is, answers that abide by the generally accepted implementation of operations. (I’ll go completely off the rails in the accompanying sidebar, but it’s not essential to the topic of browsers and will not be on either the midterm or the final.)

I am not now and never have been a member of the Mathematics Party, but apparently I was awake during high school and college math classes (“maths classes” for those who speak British English). So today I understand PEMDAS and how to apply the guidelines. Not being a mathematician, I have no opinion about or understanding of the premise that claims PEMDAS is wrong.

Both PEMDAS and BODMAS refer to what’s call the order of operations and they are synonyms. PEMDAS means powers, exponents, multiplication, division, addition, and subtraction. BODMAS replaces the first two items with brackets and order. It’s a list that indicates which math functions take precedence.

The trouble with PEMDAS is that most electronic calculators don’t follow the rules. It seems that most people who know more about math than I do and who say PEMDAS is wrong are referring more to how it’s taught because a literal interpretation would place multiplication before division and addition before subtraction when they should be interchangeable.

Put as succinctly as I can, to evaluate an expression, start by evaluating any expression inside parentheses, working inside to outside if more than one exists. Rules that apply outside the parentheses also apply within, so the exponents are resolved first, then multiplication and division (from left to right) and addition or subtraction (from left to right).

So consider this simple expression:

1 + 2 × 3 = 7

Those who fail to remember PEMDAS will argue that the answer is 9 and they will be wrong. Multiplication has a higher precedence than addition or subtraction, so the first operation is 2 × 3, which is 6 and then add the 1 for a correct answer of 7. But:

(1 + 2) × 3 = 9

Now parentheses are involved, so it’s the addition is performed first because it’s inside the parenthesis. 1 + 2 is 3. Multiplication is the only operation remaining, so 3 × 3 produces 9, which is the right answer.

Powers and square roots have the same order of precedence. Those who need to get deep into the weeds will deal with unary minus operations (a minus sign that’s part of the number, like minus one: -1) and serial exponents. Those are well beyond my comfort zone.

But browsers. Which browser is best? My best answer is: It depends. I could probably just stop there, but that would make for an uncommonly short article. So let’s push on. The best browser is the one that works for the user in a way that’s congruent with the user’s desires.

Click any small image for a full-size view. To dismiss the larger image, press ESC or tap outside the image.

For me, that means Vivaldi. It’s the very best possible browser for me on 21 Aug 2024, which is the day I started writing this segment. Vivaldi has been the best possible browser for me since 2022 or maybe 2021, but that doesn’t mean some other browser hasn’t been the best browser for me on some specific dates when I was visiting one particular website. It doesn’t mean that Vivaldi will be the best possible browser for me the day after you read this on the website or hear it on the podcast.

What’s important is to understand that a lot of browsers exist. Granted, with the exception of Firefox, most of them are based on Chrome. But “based on” doesn’t mean “identical to”. Opening Chrome, Edge, and Vivaldi reveals a lot of differences. A Chevy Camaro and a Cadillac ATS are the same car with different trim levels. Look below the exterior and you’ll see that the Nizzan 370Z and the Infiniti QX70 are the same basic car. Other examples include Hyundai Entourage/Kia Sedona, Ford Expedition/Lincoln Navigator, and Toyota 4Runner/Lexus GX470.

Firefox will differ a lot from any of the Chrome-based browsers, and of course there’s Safari that runs on Apple devices and uses Apple’s open-source browser engine, WebKit, which was derived from KHTML.

Beyond the big three or the big five, there are lots of other browsers you can try. Slant lists 77 and What Is My Browser has more than 150, some of which have been discontinued.

For most users the right browser will be Chrome, Edge, Firefox, Opera, Safari (Mac only), or Vivaldi. Others that may be worth considering include Brave, Ghostery, LibreWolf (based on Firefox), and Waterfox (also based on Firefox).

Vivaldi is currently the right browser for me because is offers the largest number of configuration settings and plays well with Chrome extensions. I use a lot of extensions for added privacy and security, password management, annoyance removal, website and development information, image searches, and bargain offers from my bank. The extensions would be available to any Chrome-based browser, so the primary selling point is the remarkable number of settings and customizations. Most of the settings are also available on Chrome, but they’re not as easy to access.

Vivaldi is currently the right browser for me because is offers the largest number of configuration settings and plays well with Chrome extensions. I use a lot of extensions for added privacy and security, password management, annoyance removal, website and development information, image searches, and bargain offers from my bank. The extensions would be available to any Chrome-based browser, so the primary selling point is the remarkable number of settings and customizations. Most of the settings are also available on Chrome, but they’re not as easy to access.

So far I’m willing to live with Vivaldi’s flaws, such as high memory use and occasional pages that simply stop working, requiring either that I reconnect to a site or restart the browser entirely. It also uses a lot of memory, but I have what is (by current standards) sufficient RAM.

Other Chrome-based browsers have a lot of configuration settings. Chrome has its own basic settings page, but it doesn’t include the array of settings found in Vivaldi. Advanced settings are revealed when the user types “chrome://flags” in the address bar, and an even longer list of internals URLs (some of which are settings, some of which are informational, and some of which are games) by typing “chrome://about” in the address bar.

Other Chrome-based browsers have a lot of configuration settings. Chrome has its own basic settings page, but it doesn’t include the array of settings found in Vivaldi. Advanced settings are revealed when the user types “chrome://flags” in the address bar, and an even longer list of internals URLs (some of which are settings, some of which are informational, and some of which are games) by typing “chrome://about” in the address bar.

These Chrome URLs are available in most (probably all) Chrome-based browsers instead of “chrome://”, preface the URL with “vivaldi://”, “edge://”, or the name of the browser. Or just use “chrome://” and the browser will change it for you: about, accessibility, app-service-internals, app-settings, apps, attribution-internals, autofill-internals, blob-internals, bluetooth-internals, bookmarks, bookmarks-side-panel.top-chrome, cast-feedback, certificate-manager, chrome-urls, commerce-internals, compare, components, conflicts, connectors-internals, crashes, credits, customize-chrome-side-panel.top-chrome, data-sharing-internals, device-log, dino, discards, download-internals, downloads, extensions, extensions-internals, family-link-user-internals, feedback, flags, gcm-internals, gpu, help, histograms, history, history-clusters-internals, history-clusters-side-panel.top-chrome, indexeddb-internals, inspect, interstitials, lens-search-bubble, local-state, location-internals, management, media-engagement, media-internals, memory-internals, metrics-internals, net-export, net-internals, network-errors, new-tab-page, new-tab-page-third-party, newtab, ntp-tiles-internals, omnibox, on-device-internals, optimization-guide-internals, password-manager, password-manager-internals, policy, predictors, prefs-internals, print, private-aggregation-internals, process-internals, profile-internals, quota-internals, read-later.top-chrome, safe-browsing, sandbox, serviceworker-internals, settings, shopping-insights-side-panel.top-chrome, signin-internals, site-engagement, suggest-internals, sync-internals, system, tab-search.top-chrome, terms, topics-internals, traces-internals, tracing, translate-internals, ukm, usb-internals, user-actions, version, web-app-internals, webrtc-internals, webrtc-logs, webxr-internals, and whats-new.

Edge settings are similar to what’s found in Chrome, but Microsoft has modified the user interface and the overall layout. All of the special Chrome URLs share Chrome’s default codebase, so they are exactly what someone who uses the standard version of Chrome will see.

Edge settings are similar to what’s found in Chrome, but Microsoft has modified the user interface and the overall layout. All of the special Chrome URLs share Chrome’s default codebase, so they are exactly what someone who uses the standard version of Chrome will see.

For perhaps the first time, Microsoft has a browser that’s worth considering. Granted it’s built on Chrome, but it feels faster than Chrome. There are useful features, including the ability to read a website aloud. Customization is good, but nowhere near as comprehensive as what Vivaldi offers. Even security and privacy have been boosted. Microsoft is building a lot of AI features into Edge, so this could be a plus or a minus depending on your opinion of artificial intelligence.

For perhaps the first time, Microsoft has a browser that’s worth considering. Granted it’s built on Chrome, but it feels faster than Chrome. There are useful features, including the ability to read a website aloud. Customization is good, but nowhere near as comprehensive as what Vivaldi offers. Even security and privacy have been boosted. Microsoft is building a lot of AI features into Edge, so this could be a plus or a minus depending on your opinion of artificial intelligence.

The only browser with significant differences for settings is Firefox. Of course there’s a standard settings page with all the expected options, but typing “About:Config” in the address bar will trigger a warning: “Proceed with Caution: Changing advanced configuration preferences can impact Firefox performance or security.” When you click the Accept the Risk and Continue button, you’ll be presented with a gigantic list of settings that can be changed.

The only browser with significant differences for settings is Firefox. Of course there’s a standard settings page with all the expected options, but typing “About:Config” in the address bar will trigger a warning: “Proceed with Caution: Changing advanced configuration preferences can impact Firefox performance or security.” When you click the Accept the Risk and Continue button, you’ll be presented with a gigantic list of settings that can be changed.

Firefox is unlikely to win any speed competitions and it has always consumed a lot of memory, but it has real protections against spyware built in and blocks most pop-ups. This can be a problem if you routinely use websites that depend on pop-up technology. Those sites won’t work properly until you modify Firefox so that its blocking is deactivated on specific sites.

There is, in my opinion, no best browser. That’s why I have Chrome, Firefox, and Edge installed and configured in addition to Vivaldi. The best browser for any specific website will depend on the website and on your opinion of how a browser should work.

Windows users may already keep information that once would have been relegated to a sticky note on the computer by using the Sticky Notes app. With the addition of Sticky Notes to One Note, it’s an even more compelling treat.

In 1968, Spencer Silver was trying to develop a super-strong adhesive. Instead, he created a “low-tack”, reusable, pressure-sensitive adhesive. Silver’s employer, 3M, tried for five years to figure out what it might be good for. In 1974 Art Fry suggested the adhesive as a way to anchor bookmarks. That led to Post-it notes. They were yellow simply because that’s what paper was in his office. The idea was a hit.

Although 3M’s patent expired in 1997, “Post-it” and the original yellow color are still registered company trademarks. Sticky notes are made by 3M and many other companies now. Microsoft added the concept to Windows 7 in 2009. It was cute, but no more useful than paper notes. In some ways, the electronic version was less useful because the notes disappeared when the computer was turned off, unlike Post-it notes that stuck around, literally.

Click any small image for a full-size view. To dismiss the larger image, press ESC or tap outside the image.

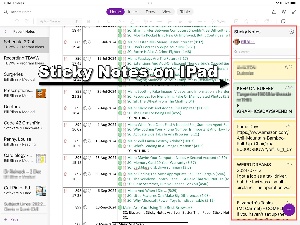

Fast forward 15 years to 2024. Microsoft updated its Sticky Notes app and linked it to OneNote, a key component of the Microsoft 365 Office Suite. Suddenly the notes aren’t limited to just the computer and you can work with them even when the computer is turned off because they’re visible in OneNote on Apple phones, Apple tablets, and Android phones.

Fast forward 15 years to 2024. Microsoft updated its Sticky Notes app and linked it to OneNote, a key component of the Microsoft 365 Office Suite. Suddenly the notes aren’t limited to just the computer and you can work with them even when the computer is turned off because they’re visible in OneNote on Apple phones, Apple tablets, and Android phones.

Until recently, I had ignored Sticky Notes on Windows because it wasn’t very helpful. Now that the notes carry over to my Windows tablet, IPad, and Android phone, it’s another helpful utility that I can’t live without. Well, that’s a bit of hyperbole and I would probably survive just fine without it, but it is surprisingly useful.

Until recently, I had ignored Sticky Notes on Windows because it wasn’t very helpful. Now that the notes carry over to my Windows tablet, IPad, and Android phone, it’s another helpful utility that I can’t live without. Well, that’s a bit of hyperbole and I would probably survive just fine without it, but it is surprisingly useful.

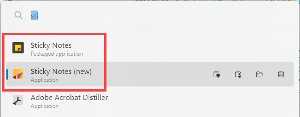

Sticky Notes is poised to become even more useful. A new version is available to Current Channel (Preview) users running OneNote on Windows Version 2402 or later. Microsoft has not announced when it will be generally available. The screenshots you’ve seen so far have been from the older version. When you search for “sti”, you’ll see two entries for Sticky Notes, one marked “new”. That’s the one you want and, if you leave it open when you power the computer off, it will launch again when you start Windows.

Sticky Notes is poised to become even more useful. A new version is available to Current Channel (Preview) users running OneNote on Windows Version 2402 or later. Microsoft has not announced when it will be generally available. The screenshots you’ve seen so far have been from the older version. When you search for “sti”, you’ll see two entries for Sticky Notes, one marked “new”. That’s the one you want and, if you leave it open when you power the computer off, it will launch again when you start Windows.

If you’re a member of the Insider program, or even if you’re not, you can read about the new version on the Microsoft 365 website.

One clever new feature remembers the application that was open when you created a note or captured a screenshot. If you decide you don’t want this feature, you can turn it off. When you revisit the document or website, Sticky Notes displays the relevant notes. This feature doesn’t always work quite as intended for documents on the computer, but the source is a clickable link if you copied text or took a screenshot on a website.

One clever new feature remembers the application that was open when you created a note or captured a screenshot. If you decide you don’t want this feature, you can turn it off. When you revisit the document or website, Sticky Notes displays the relevant notes. This feature doesn’t always work quite as intended for documents on the computer, but the source is a clickable link if you copied text or took a screenshot on a website.

Yes, I did say screenshot. When you select the screenshot option, Sticky Notes captures the window of whichever application is in use. There aren’t any options to capture just part of the application as you’ll find in dedicated screen capture applications such as SnagIt, but maybe that will be added later.

Yes, I did say screenshot. When you select the screenshot option, Sticky Notes captures the window of whichever application is in use. There aren’t any options to capture just part of the application as you’ll find in dedicated screen capture applications such as SnagIt, but maybe that will be added later.

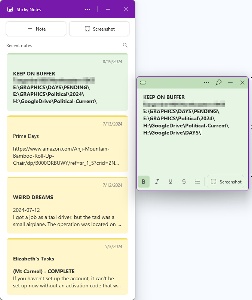

The new version has the same limited options for text formatting: Bold, italic, underline, strike-through, and bullets. The notes can be any of seven colors. An extra feature has been added to open notes: The user can resize them. It’s also possible to pin Sticky Notes to the desktop so that it’s always on top. I haven’t yet decided whether I like that option. If you’d prefer not to give it so much screen real estate, you can always open Sticky Notes by pressing the Windows key + Alt + S.

Right-clicking any note offers options to copy the note, delete it, or change the color. There’s a search icon at the top of the app, but I hope Microsoft adds the ability to drag notes up or down and to pin notes to a specific location. As it is, the notes are sorted by creation date with the most recent notes at the top.

Even if you don’t yet have access to the new Sticky Notes app, now would be a good time to experiment with the older version to see if there are ways to work this handy little app into your workflow.

The thought of a phony email address may seem questionable, but it’s easily the best way to avoid giving your address to someone you may not want to have it.

Consider this: You see an ad for something on the internet. You’re interested, but you’ve never heard of the company. You could sign up for their newsletter, but they might not stop sending messages if you decide you’re no longer interested. Or they could sell your address to spammers and scammers. But you’re still interested.

That’s one reason to use DuckDuckGo Email Protection.

Click any small image for a full-size view. To dismiss the larger image, press ESC or tap outside the image.

It’s a free email forwarding service that removes multiple types of hidden email trackers and lets you create unlimited number of unique private email addresses on the fly and makes your existing email account and inbox more private. It doesn’t matter what kind of email account you have — Gmail, Outlook, Apple, Proton, or your own private IMAP or POP3 account.

It’s a free email forwarding service that removes multiple types of hidden email trackers and lets you create unlimited number of unique private email addresses on the fly and makes your existing email account and inbox more private. It doesn’t matter what kind of email account you have — Gmail, Outlook, Apple, Proton, or your own private IMAP or POP3 account.

There are two kinds of Duck accounts: Consider one your primary account and you’ll have an address something like YourName@duck.com. Any message sent to that address will be stripped of tracking information and instantly forwarded to your standard email address. The other is a one-time address you can generate for a specific sender, and it will look something like RandomCharacters@duck.com. Messages sent to this address also will be stripped of tracking information and instantly forwarded to your standard email address. If the sender turns out to be unreliable or unwanted, you can easily delete the address.

There are two kinds of Duck accounts: Consider one your primary account and you’ll have an address something like YourName@duck.com. Any message sent to that address will be stripped of tracking information and instantly forwarded to your standard email address. The other is a one-time address you can generate for a specific sender, and it will look something like RandomCharacters@duck.com. Messages sent to this address also will be stripped of tracking information and instantly forwarded to your standard email address. If the sender turns out to be unreliable or unwanted, you can easily delete the address.

Having an address you can instantly turn off without affecting your real e-mail account is helpful, but some users will appreciate the tracker removal more. What I mean by “trackers” is the method used by the sender to determine when you viewed the message. This technology can also report what device you used to view the message and other bits of information. The TechByter newsletter, which is sent by MailChimp, includes such a tracker. It lets me know what percentage of recipients opened it. That’s useful information, but I can understand why some people won’t like that. Google, Acxiom, SendInBlue, SMTP2Go, and most other mailing services also use this technique.

When you install the DuckDuckGo Privacy Essentials extension in your browser, it automatically detects email fields and give users the option to generate a unique private Duck address for protection against email address profiling.

When you install the DuckDuckGo Privacy Essentials extension in your browser, it automatically detects email fields and give users the option to generate a unique private Duck address for protection against email address profiling.

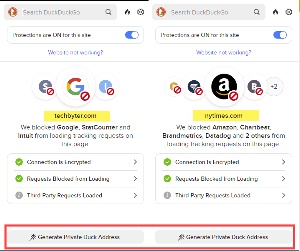

Security essentials can show information about the website such as its name, whether the connection is encrypted, and what potential trackers are being blocked. The illustration shows the results for this website and for the New York Times. You can also instantly generate a new email address that is copied to the buffer on the device.

Note that the extension is compatible with Firefox and Chrome-based browsers. That includes Microsoft’s Edge browser, but I have been unable to get it to work with Edge and Duck support has been unable to help. The extension works properly with all of the other browsers I use and with both Android and Apple mobile devices, so it’s probably a flaw in my specific installation of Edge.

Note that the extension is compatible with Firefox and Chrome-based browsers. That includes Microsoft’s Edge browser, but I have been unable to get it to work with Edge and Duck support has been unable to help. The extension works properly with all of the other browsers I use and with both Android and Apple mobile devices, so it’s probably a flaw in my specific installation of Edge.

Security Essentials and Duck email addresses are free, but you will also be encouraged to sign up for Privacy Pro ($10/month) that includes a virtual private network, a service that attempts to remove your personal information online, and assistance if your identity is ever stolen. There are no tricks, not even any requirement to opt out to avoid signing up. If you want the pro version, you have to actively seek it out. For more information, to download Security Essentials, or to sign up for email forwarding, visit the DuckDuckGo website.

TechByter Worldwide is no longer in production, but TechByter Notes is a series of brief, occasional, unscheduled, technology notes published via Substack. All TechByter Worldwide subscribers have been transferred to TechByter Notes. If you’re new here and you’d like to view the new service or subscribe to it, you can do that here: TechByter Notes.