Listen to the Podcast

23 August 2024 - Podcast #896 - (15:15)

It's Like NPR on the Web

If you find the information TechByter Worldwide provides useful or interesting, please consider a contribution.

If you find the information TechByter Worldwide provides useful or interesting, please consider a contribution.

If you’ve ever experienced an inexplicable performance problem with a computer, one that has a mysterious cause that you just can’t manage to identify, maybe it’s time to create a new account on the computer.

I had been wrestling with such a problem for several months. It included random slow keyboard response, lagging mouse movements, and astonishingly slow displays in Photoshop. No blue screens. No sudden black-screen crashes. Just a general lack of responsiveness.

The computer has 64GB of RAM. The CPU is an Intel 11th generation i9 running at 2.6GHz. The GPU is an Nvidia RTXA3000 device with 6MB of memory, so it’s not the fastest GPU on the block, but it’s more than adequate for my needs.

The Windows Resource Monitor shows no application that’s using excessive resources and the overall load on the system is well within standard operating requirements. But the system’s overall Passsmark score is just under 7000, which puts it in the 74th percentile. CPU is 57th percentile, 3D graphics 67th percentile, and disk 74th percentile. But 2D graphics are in the 46th percentile and RAM is only in the 33rd percentile. That’s unexpected given the computer’s specs.

The Windows Resource Monitor shows no application that’s using excessive resources and the overall load on the system is well within standard operating requirements. But the system’s overall Passsmark score is just under 7000, which puts it in the 74th percentile. CPU is 57th percentile, 3D graphics 67th percentile, and disk 74th percentile. But 2D graphics are in the 46th percentile and RAM is only in the 33rd percentile. That’s unexpected given the computer’s specs.

I thought the Resource Monitor would show one or more applications that were needlessly burdening the computer, but that wasn’t the case. The problem most severely affected Photoshop, making the application nearly unusable because of lags that delayed the user interface’s response. Moving or resizing text or graphic elements was difficult because the modifications were no longer shown in real time. It became a frustrating exercise in click, drag, wait – click, drag, wait – click, drag, wait.

I thought the Resource Monitor would show one or more applications that were needlessly burdening the computer, but that wasn’t the case. The problem most severely affected Photoshop, making the application nearly unusable because of lags that delayed the user interface’s response. Moving or resizing text or graphic elements was difficult because the modifications were no longer shown in real time. It became a frustrating exercise in click, drag, wait – click, drag, wait – click, drag, wait.

So two options existed: (1) Perform a system recovery, which would require reinstalling applications, setting up defaults and preferences, and hoping for the best. Or (2) create a new user that will retain all of the installed applications and settings but eliminate many of the additional installed applications that start with Windows.

The system’s performance is adequate for website design, audio and video editing, word processing, and data management. Only Lightroom Classic and Photoshop suffer severe degradation, so I decided to give the new-user option a try.

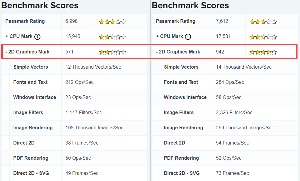

The result was surprising if not overwhelming. The Passmark score increased from slightly under 7000 to nearly 7500, about a 7% increase and the score placed the computer in the 79th percentile instead of the 74th. Still lower than what I would expect from this computer based solely on the specs.

The result was surprising if not overwhelming. The Passmark score increased from slightly under 7000 to nearly 7500, about a 7% increase and the score placed the computer in the 79th percentile instead of the 74th. Still lower than what I would expect from this computer based solely on the specs.

Looking at before and after values for the various subsystems, 2D graphics performance increased 65%, from 571 to 942. That suggested Photoshop’s performance would see a significant improvement.

Looking at before and after values for the various subsystems, 2D graphics performance increased 65%, from 571 to 942. That suggested Photoshop’s performance would see a significant improvement.

Values for CPU performance, 3D graphics, memory, and disk all edged up slightly, CPU from just under 16,000 to 17,200, 3D from 14,300 to 15,400, and disk from 21,500 to a little less than 23,000. Memory speeds were up about 4%, from 2300 to 2400.

The numbers are one thing, but what about the actual performance? I was surprised by how much more responsive Photoshop is when I use the new account. Obviously this is a workaround because I need to switch users when I want to use Photoshop. And clearly the actual problem involves an application or service that runs in my primary account but not in the new account.

The numbers are one thing, but what about the actual performance? I was surprised by how much more responsive Photoshop is when I use the new account. Obviously this is a workaround because I need to switch users when I want to use Photoshop. And clearly the actual problem involves an application or service that runs in my primary account but not in the new account.

Yes, I’ll need to do more research sometime, figure out what the actual cause is, and decide whether I want to fix the problem or live with the workaround. But creating the new account provided a solution that’s good enough for now.

When I bought a 1.5TB SanDisk Ultra MicroSDXC memory card, I was surprised to see that it came with a 10-year warranty. I probably shouldn’t have been surprised.

Maybe the first question you’re asking is about why I thought there was a need for a 1.5TB data device the size of my thumbnail. It’s because I was running out of disk space on a Surface Pro tablet computer. The Surface Pro has a small disk drive, just half a terabyte, and I had enhanced that by adding another half terabyte with a secure digital card. But it’s been a few years, prices have dropped, and I was running out of space on the tablet’s drive D.

Maybe the first question you’re asking is about why I thought there was a need for a 1.5TB data device the size of my thumbnail. It’s because I was running out of disk space on a Surface Pro tablet computer. The Surface Pro has a small disk drive, just half a terabyte, and I had enhanced that by adding another half terabyte with a secure digital card. But it’s been a few years, prices have dropped, and I was running out of space on the tablet’s drive D.

First I considered buying a 1TB replacement for $85, but found an extra $20 would buy 50% more space, so I’d be tripling the size of the D drive, not just doubling it. That was an easy decision. It arrived the next day, I copied all of the data from the half-terabyte drive to the new drive, and installed it in the tablet computer.

So let’s move on to why a 10-year warranty sounds extraordinary, but isn’t.

The first thumb drives held an amazing (at the time) 16MB of data and sold for about $50. This was in 1999 or 2000. So that’s $3.13 per megabyte. Today you’ll find a 10-pack of 1GB thumb drives for $20. If I did the math right, that’s $2.00 per gigabyte or $0.002 per megabyte. Secure digital cards are generally more expensive than thumb drives, but there’s a 32GB SanDisk Ultra MicroSDXC memory card for a little less than $8.00. Such a card would easily have been priced around $100 not many years ago.

The first thumb drives held an amazing (at the time) 16MB of data and sold for about $50. This was in 1999 or 2000. So that’s $3.13 per megabyte. Today you’ll find a 10-pack of 1GB thumb drives for $20. If I did the math right, that’s $2.00 per gigabyte or $0.002 per megabyte. Secure digital cards are generally more expensive than thumb drives, but there’s a 32GB SanDisk Ultra MicroSDXC memory card for a little less than $8.00. Such a card would easily have been priced around $100 not many years ago.

Keep those numbers in mind. I’ll come back to that in a bit.

As is the case with guarantees and warranties for data storage products, only the physical device is covered. There’s no provision for data recovery, and that’s as it should be. Users are responsible for securing their own data. The warranty will replace the drive. It’s up to you to restore the data from backup.

That’s one of several reasons why the 10-year warranty shouldn’t be either a surprise or a big deal. Data storage is a lot more reliable now than it once was. This is true for mechanical disk drives and solid-state storage, so it’s less likely that the manufacturer will have to deal with a warranty replacement. That’s good for everyone concerned.

Because data recovery isn’t included, what looks like an extended warranty can be offered with little risk to the manufacturer. If a storage device fails and the files haven’t been backed up, recovery will be astonishingly expensive and may not even be possible. But that’s not the manufacturer’s concern.

And third, there’s the cost. A storage device that once sold for $100 now costs less than a tenth of that. Manufacturers assume that the cost per unit of storage will continue to decline. So the drive that costs $100 today and was manufactured for $60 or so, will have a much lower manufacturing cost in five or ten years. Replacing a small number of failed devices over a decade can easily be built into the selling price, and that’s just for the even smaller number of consumers who will recall the 10-year warranty and act on it instead of just paying for a replacement.

The warranty isn’t quite a sales gimmick, but it’s only a minor selling point.

When looking for a new or replacement disk drive, you’re probably interested in reliability regardless of the disk drive’s warranty. Online backup provider Backblaze offers some clues.

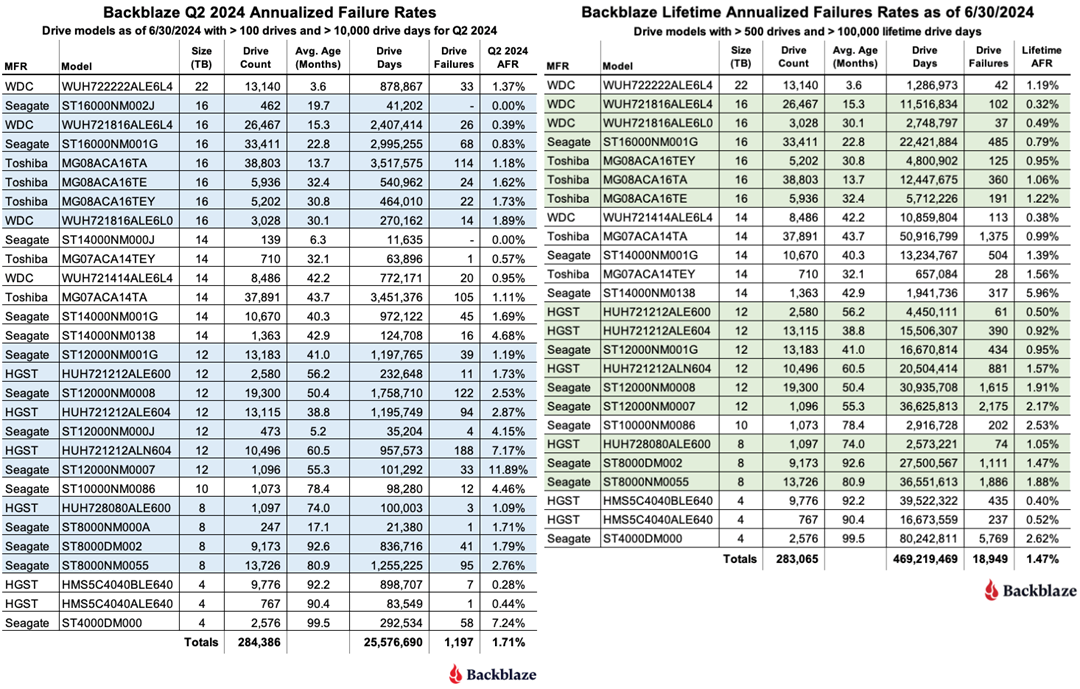

Backblaze, the organization I use for online, continuous backup publishes a quarterly report that summarizes hard drive failure rates for a lot of commonly used disk drives. The report for the second quarter was released when I was writing about 10-year warranties for secure digital cards. Most mechanical disk drives have three- or five-year warranties.

The report is worthwhile because Backblaze has a lot of drives in operation. The company lists 288,665 hard drives (HDDs) and solid state drives (SSDs) in their servers at various locations around the globe. The survey disregards 3789 boot drives, consisting of just under 3000 SSDs and nearly 900 mechanical hard drives. So the report examines 284,876 hard drives.

The drives range in size from 4TB to 22TB from HGST, Seagate, Toshiba, and Western Digital. During the second quarter, Backblaze recorded 1197 disk failures, or 1.7% of the drives in operation. The operational disk drives range in age from just under 4 months to 99.5 months. And yes, that means some of the disk drives have been running for more than 8 years.

The report describes a normal failure profile: “[T]he 8TB Seagate (blue line, model: ST800DM002) [... has a] failure rate for the first 60 months [that] was consistently around 1.0%, Seagate’s predicted [annualized failure rate]. After 60 months, the AFR increased as the drive aged as [expected].”

Failure rates range from 0% to nearly 12% among the various manufacturers and models. Often the drives with the lowest apparent failure rate are models with few drives in service. One Seagate model with a 0% failure rate had just 462 in operation. Age also clearly has an effect on the failure rate. Another Seagate model with 1096 drives in operation had the 11.9% failure rate, but the drives have an average age of nearly 5 years.

The report says “In Q2 2024, two drive models had zero failures, a 14TB Seagate (model: ST14000NM000J) and a 16TB Seagate (model: ST16000NM002J). Both have a relatively small number of drives and drive days for the quarter, so their success is somewhat muted, but the 16TB Seagate drive model has a very respectable 0.57% lifetime failure rate.”

Backblaze has been recording and reporting disk information for more than a decade. The reports examine telemetry data of the drives, including their SMART stats and other health-related attributes. The reporting process does not read or otherwise examine any customer data stored on the drives. The full dataset can be downloaded from Backblaze’s Drive Stats web page.

So if you’re in the market for a new disk drive, the report from Backblaze can be a useful resource.

TechByter Worldwide is no longer in production, but TechByter Notes is a series of brief, occasional, unscheduled, technology notes published via Substack. All TechByter Worldwide subscribers have been transferred to TechByter Notes. If you’re new here and you’d like to view the new service or subscribe to it, you can do that here: TechByter Notes.