Listen to the Podcast

1 Sep 2023 - Podcast #847 - (20:09)

It's Like NPR on the Web

If you find the information TechByter Worldwide provides useful or interesting, please consider a contribution.

If you find the information TechByter Worldwide provides useful or interesting, please consider a contribution.

Buying a new computer isn’t unlike buying a new car. Define needs, identify suitable models, and consider useful options. Only then is it time to make the purchase.

At one time, the best advice was to first identify the software you needed and to use that information to determine what kind of computer to buy. That’s less useful now because most applications run on both Windows and MacOS computers, and many run on Linux systems, too.

There may be nothing to decide because those who have used MacOS computers for a long time generally should stick with Apple, those who have used Windows for years, should probably stick with Microsoft. Likewise, for those who use one of the hundreds of Linux variants.

I know people who have switched from Windows to the MacOS and often they’ve been unhappy because things don’t work the way they’ve become accustomed to. MacOS users who find a need to use a Windows computer can have similar issues. Switching to or from Linux is equally fraught. I'm a big fan of sticking with what you’re familiar with.

You’ll have more decisions to make with a Windows computer, which can be good or bad, but some of the basic decisions are the same regardless. Because there are more decisions to make with a Windows system, that’s what I’ll describe here.

Click any small image for a full-size view. To dismiss the larger image, press ESC or tap outside the image.

How important is portability? Think about how you will use the computer. Will you use it mainly to browse the web, pay bills online, send email, and visit social networking sites? Or will you organize, edit, and share digital photos, watch streaming video, and work with complex spreadsheets and documents? Maybe you want to get into video production and high-end video editing, or you’re an intense gamer.

How important is portability? Think about how you will use the computer. Will you use it mainly to browse the web, pay bills online, send email, and visit social networking sites? Or will you organize, edit, and share digital photos, watch streaming video, and work with complex spreadsheets and documents? Maybe you want to get into video production and high-end video editing, or you’re an intense gamer.

More complex and demanding tasks call for more processing power, memory, and disk storage.

Many big manufacturers and hundreds of smaller shops build custom desktop computers. Not as many companies build notebooks, so you’ll be limited to fewer than a dozen such as Acer, Dell, Hewlett-Packard, Lenovo, Microsoft, and Toshiba.

Notebook computers are portable, but desktop systems cost less for the same features and can be upgraded more easily. No manufacturer is inherently better than any other. All manufacture powerful, high-end computers and most also make limited, low-end computers. Specs are more important than brand.

If portability is essential or space is limited, a notebook computer is probably the better choice. Otherwise, a desktop system is likely to be less expensive, easier to maintain, and more powerful.

The central processing unit (CPU) runs the show and I usually buy a bit more processing power and RAM than I need immediately because I know I’ll need more later. A word processor in the late 1980s likely consumed less than 100KB of memory and ran well on an Intel 8088 processor. Today’s Microsoft Word easily consumes 200MB of memory and will be sluggish on low-end processors.

The central processing unit (CPU) runs the show and I usually buy a bit more processing power and RAM than I need immediately because I know I’ll need more later. A word processor in the late 1980s likely consumed less than 100KB of memory and ran well on an Intel 8088 processor. Today’s Microsoft Word easily consumes 200MB of memory and will be sluggish on low-end processors.

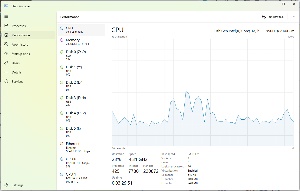

Browsers are memory hogs. As I was writing this article, Firefox and Vivaldi were each using more than 2GB of RAM. That’s a lot of memory, but the two browsers combined were using less than one percent of the CPU.

Today’s applications have more features than their predecessors had, and programmers use languages and techniques that make development easier and faster at the cost of creating applications that need far more system resources to run.

The two primary manufacturers of CPUs are Intel and AMD. If the computer will be used solely for email and internet browsing, an Intel Core i3 or an AMD Ryzen 3 may be adequate, but the Intel Core i5 or AMD Ryzen 5 will be a better choice for most users. Those who need more power for gaming or photo editing should consider the Core i7 from Intel or the Ryzen 7 from AMD. For top performance, check out the Intel Core i9 or the AMD Ryzen 9.

Most processor models are offered with different numbers of cores and various operating speeds. More cores and faster speeds mean the computer will run faster. An 8-core Intel i9 running at 3.5GHz will cost around $325 while a 24-core i9 running at 5.8GHz will cost double that. The best overall price-performance will often be the most powerful or second-most-powerful CPU with an operating speed one or two steps down from the maximum. An extra bit of CPU speed is rarely worth the cost.

How much disk space you need depends on how much disk space you need. That’s the painfully obvious way of saying your needs are unique.

How much disk space you need depends on how much disk space you need. That’s the painfully obvious way of saying your needs are unique.

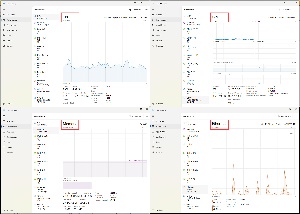

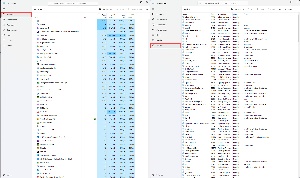

Look at how much disk space you’re using now. Here’s an example from my computer, which has six disk drives, internal and external. These are numbered 0 through 5 and there are eight drive letters (C through I and Y) because drives 3 and 4 each have two partitions.

Sum the sizes of all the disk drives and the amount of free space. Drive C, for example, starts with 952GB and the unused space is 640GB. I disregard drive Y because it’s used as a temporary backup.

So the total size of all working disks is 10,988GB and the total free space is 5216GB, which means nearly half of the disk space (47%) is free.

If half or more of the disk space on your computer is free, you’ll need about the same amount of space on your new computer unless your storage requirements will be changing.

I have tens of thousands of large digital photographs, about 34,000 audio tracks (not including files used for the production of TechByter Worldwide), a lot of video files and some entire motion pictures, and more than 168,000 files that represent applications and operating systems downloaded over the past several decades.

Your requirements will differ from mine, but the process and guidelines are the same: Try to keep about half of the disk space free and never let free space drop to less than 15%. A disk that’s nearly full will be much slower than one with adequate free space.

Consider the type of graphics card you need. Virtually all computers include “integrated graphics” on the motherboard, but many also have a dedicated graphics processing unit (GPU). If you do a lot of photo editing or video editing, the GPU is critical. Most are made by Nvidia and AMD, and prices vary a lot.

Consider the type of graphics card you need. Virtually all computers include “integrated graphics” on the motherboard, but many also have a dedicated graphics processing unit (GPU). If you do a lot of photo editing or video editing, the GPU is critical. Most are made by Nvidia and AMD, and prices vary a lot.

Low-end GPU cards for desktop computers cost less than $100; at the other end of the spectrum, the Asus Nvidia GeForce RTX 4090 costs nearly $2200. Choices for notebook computers will be more limited. The video subsystem you choose may also depend on the number of monitors you want to use. I prefer at least two monitors, even for a notebook computer.

Make sure the computer has enough USB ports for all the devices you need to connect to it and that the network connections are fast enough to support the speed from your internet service provider.

If the computer has too few ports, you may need to purchase a dock for a notebook computer or a port expansion unit for a desktop.

Does the computer need an optical drive? Few computers have a built-in optical drive now because software is rarely distributed on physical media. If you use CDs and DVDs, or you need to create them, you’ll need an optical drive. These can be built in to desktop systems, but most notebook computers do not have an optical drive option and can accommodate one only as an external device.

Take all the time you need to think about your requirements. That’s the best way to ensure that the computer you buy will be one that pleases you for many years.

This article is being published simultaneously in the September issue of the Blinn Communications newsletter.

“Any time spent waiting on a computer is wasted.” That’s an old saying that probably dates back almost to the creation of the first computer. With such powerful hardware, why do computers sometimes seem so slow?

Computers that ran DOS seemed fast, at least in my memory. But now they sometimes are annoyingly slow. Why?

The most basic reason is that we ask computers to do more than we used to. A DOS computer ran one application at a time and many applications were written in a low-level assembler language. Switching between a word processor and a spreadsheet required shutting down the word processor, inserting a different disk in drive A, and starting the spreadsheet program.

Terminate-and-stay-resident (TSR) applications came along in the 1980s so more than one application could be in the computer’s memory simultaneously, but switching between them was clumsy and frequently caused the computer to crash. Now your computer is probably running hundreds of applications, processes, and services simultaneously—and it doesn’t crash. Most of the time, anyway.

Click any small image for a full-size view. To dismiss the larger image, press ESC or tap outside the image.

When I was writing this segment, I counted nearly 30 active applications and a nearly untold number of background processes and services: 1Password, Q-Dir, Thunderbird to collect mail from seven accounts, the Vivaldi browser with 21 open tabs, OneNote, UltraEdit Studio for writing this article, Beeper, Microsoft Phone Link, Filezilla, SnagIt, Skype, Messenger, Mailwasher Pro to monitor six email accounts, Fx Sound, Open Hardware Monitor, several PowerToys components, Google Drive, Microsoft One Drive, WinGetUI, CrashPlan, Unchecky, Nord VPN, Desktop OK, Break Timer to remind me to stand up occasionally, Aero Clock, GoodSync, and Macro Express Pro. Additionally there are background services such as those for Focusrite audio components, Adobe Creative Cloud, Canon printer software, Bluetooth, Windows Security, Logitech drivers, the Windows scheduler, and on and on and on.

When I was writing this segment, I counted nearly 30 active applications and a nearly untold number of background processes and services: 1Password, Q-Dir, Thunderbird to collect mail from seven accounts, the Vivaldi browser with 21 open tabs, OneNote, UltraEdit Studio for writing this article, Beeper, Microsoft Phone Link, Filezilla, SnagIt, Skype, Messenger, Mailwasher Pro to monitor six email accounts, Fx Sound, Open Hardware Monitor, several PowerToys components, Google Drive, Microsoft One Drive, WinGetUI, CrashPlan, Unchecky, Nord VPN, Desktop OK, Break Timer to remind me to stand up occasionally, Aero Clock, GoodSync, and Macro Express Pro. Additionally there are background services such as those for Focusrite audio components, Adobe Creative Cloud, Canon printer software, Bluetooth, Windows Security, Logitech drivers, the Windows scheduler, and on and on and on.

Take a look at the Windows Task Manager on your computer and you may find several hundred background processes running, lots of services (many of them started by Windows), and maybe a dozen or more applications that you’ve added to the Windows boot process or have opened during the current session.

Fortunately, computers are much better at multi-tasking than we humans are. Your computer can deal with this kind of load unless the CPU is severely underpowered or the computer has only limited system memory.

Fortunately, computers are much better at multi-tasking than we humans are. Your computer can deal with this kind of load unless the CPU is severely underpowered or the computer has only limited system memory.

So if your computer legitimately seems to be slower than it should be, the Task Manager can show everything that’s running and which applications, processes, or services are consuming the most CPU, memory, disk, and network services.

Do you need to run all of the applications that are running? Is each tab that’s open in the browser important?

If there are applications that are open, but you rarely use them, you might be able to speed the computer a bit by not opening them until you need them. This is something that’s worth review occasionally because any time spent waiting on a computer is wasted. That’s actually my justification for keeping a lot of applications open: I prefer a computer that’s imperceptibly slower than it might be to having to wait for an application to open.

The Task Manager will help you sort this out and devise a configuration that works best for you.

When a computer is misbehaving, Safe Mode is helpful in diagnosing the problem and may be instrumental in fixing it.

Safe Mode isn't just a Windows thing. MacOS computers have a safe mode. So do computer that run one of the many Linux variants, but I'll be describing the Safe Mode provided by Microsoft.

When you start a computer in safe mode, it loads the absolute minimum drivers, services, and applications required to run. That makes it useful in determining what is causing a problem. Those whose experience dates back to Windows 95 may remember that pressing F8 during the boot process activates Safe Mode. Well, at least it used to.

Security measures and the move to Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) starting with Windows 8 has eliminated that capability. If your computer still uses the Basic Input Output System (BIOS) and has a mechanical hard drive, F8 should still work.

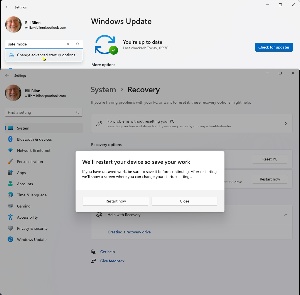

Windows will automatically invoke Safe Mode if the computer fails to boot three consecutive times. On the fourth attempt, Windows enters Automatic Repair Mode and attempts to diagnose the problem. Click Advanced Options > Troubleshoot > Advanced Options > Startup Settings > Restart, and when the computer restarts, you'll see two Safe Mode options: Safe Mode and Safe Mode With Networking.

Click any small image for a full-size view. To dismiss the larger image, press ESC or tap outside the image.

When the computer has significant problems, but is able to boot, you can invoke Safe Mode on Windows 11 by opening Settings and typing safe mode into the search panel and then choosing Change advanced startup options. Before moving on to Safe Mode, you may want to try the troubleshooter option. If that doesn't help, choose Restart Now and follow the instructions as they appear on screen.

When the computer has significant problems, but is able to boot, you can invoke Safe Mode on Windows 11 by opening Settings and typing safe mode into the search panel and then choosing Change advanced startup options. Before moving on to Safe Mode, you may want to try the troubleshooter option. If that doesn't help, choose Restart Now and follow the instructions as they appear on screen.

Assuming you use the Windows 11 logon screen, hold the Shift key down, click the Power button, and choose Restart. When the computer restarts, you'll see two Safe Mode options: Safe Mode and Safe Mode With Networking.

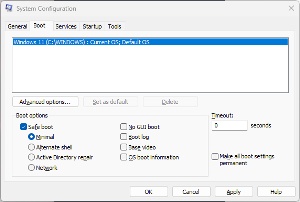

Another good way to get to Safe Mode if the troubled computer still boots involves using System Configuration. Press the Windows key, type msconfig, and press Enter. Select the Boot tab, Enable Safe Boot, and choose any options. The options available:

Another good way to get to Safe Mode if the troubled computer still boots involves using System Configuration. Press the Windows key, type msconfig, and press Enter. Select the Boot tab, Enable Safe Boot, and choose any options. The options available:

To learn more about what you can do in Safe Mode, see How-To Geek's How to Use Safe Mode to Fix Your Windows PC.