Listen to the Podcast

10 February 2023 - Podcast #818 - (25:48)

It's Like NPR on the Web

If you find the information TechByter Worldwide provides useful or interesting, please consider a contribution.

If you find the information TechByter Worldwide provides useful or interesting, please consider a contribution.

You need a password manager. I've said that repeatedly and my recommendation for years has been LastPass. I still say that you need a password manager, but LastPass is no longer my choice or my recommendation.

LastPass had nearly 26 million users late in 2022. If you're still in that group, now is the time to think about leaving. Several other password managers exist and switching isn't as hard as you might expect. When I replaced LastPass with 1Password, the import process worked well and only secure notes had to be added manually. My 400 or so passwords arrived without error.

LastPass has reported attacks previously and has generally been transparent about what happened, when, and what they're doing to mitigate the problem. But a breach that happened sometime after August of last year has not been dealt with well. For one thing, LastPass didn't reveal the exact date of the incident. Three days before Christmas, LastPass provided further information about a breach they had downplayed at the end of November. Initially, there was no indication that any user passwords had been exposed, but that changed on 22 December: The breach exposed encrypted password data.

How serious that might be depends, among other factors, on how strong a user's master password was. I had a strong master password and any brute force attack would likely be unsuccessful. The size and scope of the breach, coupled with LastPass's reticence, was sufficient for me to start looking seriously at other password managers, specifically 1Password and Bitwarden.

The most recent LastPass breach also revealed some other customer data such as names, email addresses, phone numbers, and billing information. URLs are revealed, too, because LastPass doesn't encrypt them. This oversight would give crooks an advantage. Instead of trying to crack the password for DuoLingo, they would concentrate on cracking the password for American Express.

Click any small image for a full-size view. To dismiss the larger image, press ESC or tap outside the image.

In previous breaches, simply changing the master password was sufficient to continue protecting login information. Changing the master password won't do any good this time because the crooks already have the encrypted data. If you continue to use LastPass, it's important to change the master password and the passwords for any accounts that contain health, financial, or personal identification data. If you switch to a new password manager, be sure to change passwords for these kinds of accounts and, when two-factor authentication is available, use it.

In previous breaches, simply changing the master password was sufficient to continue protecting login information. Changing the master password won't do any good this time because the crooks already have the encrypted data. If you continue to use LastPass, it's important to change the master password and the passwords for any accounts that contain health, financial, or personal identification data. If you switch to a new password manager, be sure to change passwords for these kinds of accounts and, when two-factor authentication is available, use it.

Some advisors recommend changing all of your passwords, but anyone who has hundreds of passwords probably won't want to spend the time doing that. Each password change takes a few minutes — let's say 3 minutes — so I would have to spend 20 hours to change my 400 or so passwords. Instead, I've changed the ones for banks, government agencies, credit reporting businesses and and other high-value targets, but I haven't bothered with those for newspapers, weather services, and libraries.

LastPass worked well for many years. When it was acquired by LogMeIn, changes were made so that the free version would be all but unusable. Then, venture capitalists Francisco Partners and Evergreen Coast Capital Corp spun LastPass off as an independent business with the goal of maximizing value for later sale. I wonder how that's working out for them now.

Whether it's LastPass or another password manager, having one is essential. LastPass, when coupled with a very strong master password and two-factor authentication on critical accounts, is still safe, but there are other choices.

I decided it was time to move on, so I looked mainly at 1Password and Bitwarden. 1Password has a 2-week free trial and Bitwarden has a totally free option. Bitwarden is an open-source project, so anyone can obtain the source code and review it. 1Password's code is proprietary. Both have apps for Windows, MacOS, Linux, Android, and IOS as well as extensions for all major web browsers. 1Password also has a version for ChromeOS.

1Password's most welcome feature is its ability to be an authenticator app such as Authy or the Google Authenticator. As much as I value the added protection of two-factor authentication, I recognize the process can be a bit clumsy. Using LastPass, I would select and launch a site with two-factor authentication. LastPass would provide the user ID and password, but then I would have to open Authy, find and select the site I wanted to open, click the icon to copy the time-limited code to the clipboard, return to the browser, and paste the code in to open the site.

1Password's most welcome feature is its ability to be an authenticator app such as Authy or the Google Authenticator. As much as I value the added protection of two-factor authentication, I recognize the process can be a bit clumsy. Using LastPass, I would select and launch a site with two-factor authentication. LastPass would provide the user ID and password, but then I would have to open Authy, find and select the site I wanted to open, click the icon to copy the time-limited code to the clipboard, return to the browser, and paste the code in to open the site.

1Password eliminates several of those steps. I select and launch the site and 1Password fills in the user name and password. When the site asks for the second-factor code, 1Password provides it and the site opens. No additional effort is required and the process takes less than a second.

Because every website designer has a different way to implement two-factor authentication, the most difficult part of the process may be setting it up. The good news is a non-profit organization, the 2factorauth Group, maintains a website with pointers to instructions from a gigantic number of websites. 2factorauth Group says its mission is "to be an independent source of information on which services support MFA/2FA [multi-factor/two-factor authentication] and help consumers demand [it] on the services that currently don’t."

Because every website designer has a different way to implement two-factor authentication, the most difficult part of the process may be setting it up. The good news is a non-profit organization, the 2factorauth Group, maintains a website with pointers to instructions from a gigantic number of websites. 2factorauth Group says its mission is "to be an independent source of information on which services support MFA/2FA [multi-factor/two-factor authentication] and help consumers demand [it] on the services that currently don’t."

In reviewing and updating two-factor authentication for the sites I use, I was reminded that not a single one of the banks or financial institutions I use offers 2FA. The 2factorauth Group shows clearly how behind the times most banks are. The listing of banking sites shows that many financial institutions don't offer any type of two-factor authentication and that when it's available, most have only SMS, phone, or email options. A few such as Bank of America and Morgan Stanley have hardware options, but virtually none work with software authenticator services.

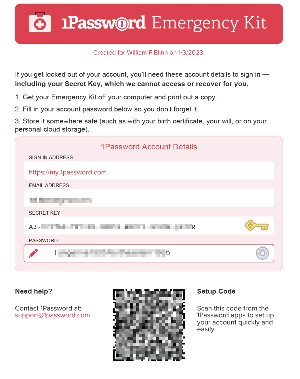

When you sign up for 1Password, you'll receive a PDF document called an emergency kit. It contains the login address, your email address (which is your user name), a long and complex secret key generated by 1Password, and a space where you can write in your password, which should also be long and complex. The secret key is used to encrypt your data; only you and the 1Password application know the key. It's needed to decrypt your private information. If you lose it or your master password, nobody will be able to decrypt your data — not even 1Password.

When you sign up for 1Password, you'll receive a PDF document called an emergency kit. It contains the login address, your email address (which is your user name), a long and complex secret key generated by 1Password, and a space where you can write in your password, which should also be long and complex. The secret key is used to encrypt your data; only you and the 1Password application know the key. It's needed to decrypt your private information. If you lose it or your master password, nobody will be able to decrypt your data — not even 1Password.

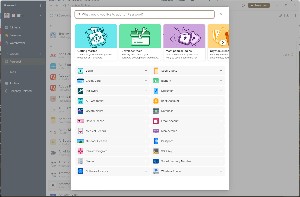

To add an item to 1Password, you first specify what kind of information you'll be storing. For most people, login information will probably be the one that's used the most, but there are also options for secure notes, passports, email accounts, bank accounts, credit cards, and medical records — 22 options in all. Each type has fields to store specific types of information that are relevant: license number, type, restrictions, state, and expiration date for a driver license; cardholder name, card number, security code, PIN, expiration date, and bank for a credit card. The user can add or delete fields as desired.

To add an item to 1Password, you first specify what kind of information you'll be storing. For most people, login information will probably be the one that's used the most, but there are also options for secure notes, passports, email accounts, bank accounts, credit cards, and medical records — 22 options in all. Each type has fields to store specific types of information that are relevant: license number, type, restrictions, state, and expiration date for a driver license; cardholder name, card number, security code, PIN, expiration date, and bank for a credit card. The user can add or delete fields as desired.

Some password managers include the ability to check for compromised websites and passwords and to highlight re-used passwords or weak passwords. 1Password's Watchtower does this, and also adds warnings when a site in your vault offers two-factor authentication but you haven't enabled it. In other words, it alerts you when problems exist that you might otherwise miss.

Some password managers include the ability to check for compromised websites and passwords and to highlight re-used passwords or weak passwords. 1Password's Watchtower does this, and also adds warnings when a site in your vault offers two-factor authentication but you haven't enabled it. In other words, it alerts you when problems exist that you might otherwise miss.

1Password costs $36 per year or $60 a year for families, which gives up to five people their own individual accounts.

Other options are Bitwarden that I mentioned earlier. There's a free version with some restrictions and a $40 annual plan that's good for the whole family. Because it's an open source application, anyone can see the code and more eyes on the code means that more flaws are found and corrected.

Dashlane costs $40 per year ($90 for families), but there is a free option. Although Dashlane has no desktop app, it works with all major browsers and apps are available for IOS and Android. There's a 30-day free trial if you want to test it.

KeePassXC is a free, open-source application. There's a desktop app for Windows, MacOS, and Linux. You're responsible for creating and storing the password vault. Extensions are available for Firefox and Chrome-based browsers. Although there are no apps for IOS or Android from the developers, KeePass2Android and Strongbox for IPhone are available separately from the appropriate stores.

Although I have stopped using LastPass, you might want to avoid the bother of switching apps. If your master password was long and complex, you're probably safe. Still, at the very least you should change both the master password, which does nothing to protect against the recent breach, and the passwords for all critical, high-value sites. Once you've done that, LastPass is probably safe.

The graphical user interface is a big improvement over the days when everything was in plain text, but sometimes it helps to know some of the old ways. The command prompt can quickly display information that not always easy to find otherwise. Here are a few commands that everyone should know or have a cheat sheet for.

Click any small image for a full-size view. To dismiss the larger image, press ESC or tap outside the image.

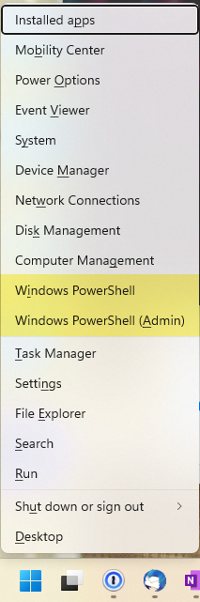

We should start with opening a Command window because you'll need to have it open. The easiest way involves pressing the Windows key and X. You'll see a list of options including either "Command Line" and "Command Line as Administrator" or "Windows PowerShell" and "Windows PowerShell as Administrator". If you've set Windows to use PowerShell instead of Command, as I have, you'll get the PowerShell option; otherwise, you'll be offered Command. PowerShell understands many of the old Command Line commands and a lot of Linux commands in addition to PowerShell commands.

We should start with opening a Command window because you'll need to have it open. The easiest way involves pressing the Windows key and X. You'll see a list of options including either "Command Line" and "Command Line as Administrator" or "Windows PowerShell" and "Windows PowerShell as Administrator". If you've set Windows to use PowerShell instead of Command, as I have, you'll get the PowerShell option; otherwise, you'll be offered Command. PowerShell understands many of the old Command Line commands and a lot of Linux commands in addition to PowerShell commands.

Some of the commands I'll describe here do not work with PowerShell, so maybe it's better to use the option that will always open the Command Line. Just press the Windows key, type "cmd", and click Run as Administrator for Command Prompt.

Why as Administrator? That's my default choice because some of the commands require administrator privileges. Running the System File Checker (SFC) or the Deployment Image Servicing and Management module (DISM) requires heightened permissions, for example. Although many of the commands don't need to be run as Administrator, I've found it easier to just start as Administrator when I pull out the Command Line or PowerShell. Running either as Administrator will require that you approve a User Access Control warning.

If you use PowerShell, the current version is 7, but the default version that Windows will run is 5. This can be changed by migrating to the latest version, but you can ignore that unless you're a PowerShell developer — in which case you've probably already migrated and will be bored by all this blathering.

Now that you have a Command Prompt (or possibly a PowerShell 5 or 7 command line), you may be wondering what you can do.

I've mentioned SFC and DISM previously. I run these commands at least once per month:

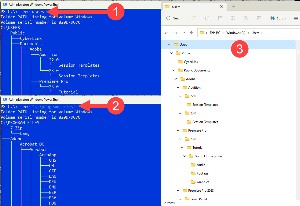

Examining a disk drive's or directory's structure can be helpful and the tree command tree d: will display all of the directories on the D drive. To limit the listing to a single directory, add it to the command line (1) tree c:\users to display all of the directories in the Users directory or (2) tree "c:\Program Files" to display all of the directories in the Program Files directory. When a directory name includes a space, the name needs to be surrounded by quotation marks.

Examining a disk drive's or directory's structure can be helpful and the tree command tree d: will display all of the directories on the D drive. To limit the listing to a single directory, add it to the command line (1) tree c:\users to display all of the directories in the Users directory or (2) tree "c:\Program Files" to display all of the directories in the Program Files directory. When a directory name includes a space, the name needs to be surrounded by quotation marks.

The Windows File Explorer can also display the file structure, but some people (including me) prefer the tree command. In File Explorer, (3) navigate to the drive or directory you want to view and press Ctrl-Alt-Right Arrow to expand all of the directories and Ctrl-Alt-Left Arrow to collapse all the directories.

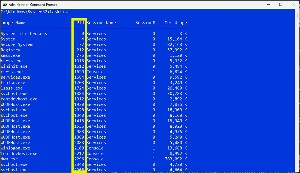

You know that computers are quite busy with foreground and background tasks. You can see a list with the Task Manager, but there's also an option to view the list with the Command line.

You know that computers are quite busy with foreground and background tasks. You can see a list with the Task Manager, but there's also an option to view the list with the Command line.

tasklist displays a list of running tasks, the process ID, session name, session number, and the amount of memory the task consumes. The process ID (PID) can be used to kill the task.

tasklist displays a list of running tasks, the process ID, session name, session number, and the amount of memory the task consumes. The process ID (PID) can be used to kill the task.

To see more detailed information add /v (for verbose) after the command to add status information, the name of the user that's running the process, CPU time, and the window title. Additionally there are options for output format and the ability to filter the results.

If there's a process you want to terminate type taskkill followed by /PID and the process ID. It's possible to kill multiple processes simultaneously using the image name and filters.

A word of caution might be worthwhile here: Don't kill random processes.

In the old days, when DOS is all there was, batch files could be used to create menu systems for starting programs and the prompt could be modified to make the computer more respectful. Now that the Command Prompt runs in a window, the title can also be modified.

title Grand Wizard changes the window's title from Administrator: Command Prompt to Administrator: Grand Wizard.

title Grand Wizard changes the window's title from Administrator: Command Prompt to Administrator: Grand Wizard.

prompt Your Command, Grand Wizard$g changes the prompt from C:\Windows\System32> to Your Command, Grand Wizard>. To restore the default prompt, type just prompt and press Enter.

You'll notice promptly (sorry) that the prompt no longer indicates the current drive or directory. This can be fixed with prompt We are at $p and the time is $t$_What is your command, oh Grand Wizard?$g

Those are silly and fun, perhaps, but largely useless. Here's one that's quite useful:

Those are silly and fun, perhaps, but largely useless. Here's one that's quite useful:

powercfg /batteryreport /output "C:\mybattery.html"

This creates a file you can view with a browser to review a detailed report on the health of the computer's battery.

The old style commands can be useful and sometimes they can be amusing, perhaps even amazing. Lifewire has two useful lists, one that includes a comprehensive list of Command Line commands and a second that summarizes dozens of old-style DOS commands, some of which still work.

When you have questions about how a command works or want more detailed information about what it does, try typing the command and following it with /?. DOS is old, dating back to the early 1980s, but old doesn't mean useless. Sometimes using the command line produces the result you want faster than Windows would.

It may seem odd that in a program that starts with my reasons for switching from LastPass to 1Password, the third article is about getting rid of passwords permanently. Passwords are a mess. It's not stretching the truth much to say passwords are a disaster. We need to get rid of them and there has been some progress.

Click any small image for a full-size view. To dismiss the larger image, press ESC or tap outside the image.

Passkeys may eventually replace passwords in most cases. If you have a Microsoft account, you can delete your password now. When you start an application, you'll be told that you need to approve the action using the Microsoft Authenticator on your smartphone. Microsoft's Authenticator runs only on mobile devices, but it works well.

Passkeys may eventually replace passwords in most cases. If you have a Microsoft account, you can delete your password now. When you start an application, you'll be told that you need to approve the action using the Microsoft Authenticator on your smartphone. Microsoft's Authenticator runs only on mobile devices, but it works well.

The request is sent to your phone in about one second and as soon as you tap Approve, you're in. The obvious problem with this is that you must have your phone to use the Authenticator app. If you don't have it, there are other ways to prove that you are who you claim to be, but they require your password, PIN, or Windows Hello. I already unlock my Windows computers by showing my face to the computer and I unlock my phone with a fingerprint.

Some apps on the phone can be set up to use the device's built-in facial recognition or fingerprint reader, so we've definitely started down the road that was first described to me in the mid 1980s. It's been only 38 years or so. The creators of password managers must see that the future doesn't include them, but there's not much to fear in the short-term future.

Many enterprises have migrated to single sign-on (SSO) technologies that allow users to log in with a single ID to multiple independent software systems or applications. This is a big step forward from the days when an organization had half a dozen or more systems, each with its own password rules.

Until we get to a passwordless future, and that may not happen for another 38 years or so, we'll have to cope with systems that continue to use passwords in addition to those that can be accessed without password (such as BestBuy, Microsoft, and PayPal). Because that's the case, you're still going to need a password manager for the foreseeable future.

So sign up with a password manager, make your passwords impossible to guess, and use two-step authentication whenever it's available.