Listen to the Podcast

12 August 2022 - Podcast #805 - (18:09)

It's Like NPR on the Web

If you find the information TechByter Worldwide provides useful or interesting, please consider a contribution.

If you find the information TechByter Worldwide provides useful or interesting, please consider a contribution.

Is there a smart watch on your wrist yet? If not, one may be in your future. These devices are nowhere near as common as smart phones, but usage is increasing. I recently joined the group of owners.

Click any small image for a full-size view. To dismiss the larger image, press ESC or tap outside the image.

As of 2021, 97% of Americans owned a mobile phone of some sort and 85% of Americans owned a smart phone (Pew Research Center). By comparison, about 21% of US adults owned smart watches or fitness trackers as of 2020 (Pew Research Center). Women are somewhat more likely to own one of these devices than men, 25% to 18%.

As of 2021, 97% of Americans owned a mobile phone of some sort and 85% of Americans owned a smart phone (Pew Research Center). By comparison, about 21% of US adults owned smart watches or fitness trackers as of 2020 (Pew Research Center). Women are somewhat more likely to own one of these devices than men, 25% to 18%.

Mordor Intelligence says smart watches are gaining significant market share because manufacturers such as Apple and Fitbit are adding health-monitoring features. The report also notes that covid has pushed consumers toward connected monitoring devices.

The report notes that most smartwatches are designed to be paired with smartphones using Bluetooth so the devices can share phone notifications. Problems exist because smartwatches can usually be paired with only a limited number of compatible smartphones. Apple's watches can be paired only with Apple's phones, version 6 and later. Samsung's watches can be paired with Samsung phones, but also with most other Android phones.

Statista reports that Apple has the largest market share, but that share is declining — from nearly 33% in 2020 to about 30%. Huawei dropped from second place to third and Samsung is now in second place with about 10% of the market. Others include Imoo, Fitbit, Fossil, Noise, Garmin, and AmazFit, but the "all others" category is at 27% and increasing.

Wearing a watch — any watch — is something I've not done for a long, long time. Working full-time in radio gives one an enhanced sense of time, and I seem to have acquired a double dose of that. If anyone asked me what time it was, day or night, in the late 1960s through the mid 1980s, I could tell them and usually be within about three minutes. That capability has declined in recent years. In some cases, I'm still accurate within five minutes or so much of the time. But sometimes I'm off by several hours, particularly overnight.

But I had another reason for deciding that a smart watch would be a good investment. I'll get to that in a bit.

Because I own an Android smart phone and had no desire to adopt Apple's ecosystem, there was no reason for me to consider an Apple watch. After looking at Fitbit, Garmin, and some of the off-brand watches, I selected a Samsung Galaxy Watch. Overall, I'm pleased with how it works.

Because I own an Android smart phone and had no desire to adopt Apple's ecosystem, there was no reason for me to consider an Apple watch. After looking at Fitbit, Garmin, and some of the off-brand watches, I selected a Samsung Galaxy Watch. Overall, I'm pleased with how it works.

Because the watch connects to my phone, I can use the smart lock function that keeps the phone unlocked for up to four hours while it's connected to the watch. This is a handy feature because it actually works. Android's Smart Lock feature is supposed to keep the phone unlocked when it's at home using the "trusted place" option, but that feature fails about as often as it succeeds.

I also tried the Smart Lock option to keep the phone unlocked when it's connected to the computer. That works, but the Bluetooth connection doesn't work when I leave the room the computer is in. Because the phone and the watch go with me wherever I go, I now get a full four hours during which I don't have to repeatedly unlock the phone.

The initial setup was uncommonly easy. After charging the watch's battery and loading the Samsung Wear app on the phone, I started the watch and followed on-screen instructions as it took care of pairing itself with the phone.

The initial setup was uncommonly easy. After charging the watch's battery and loading the Samsung Wear app on the phone, I started the watch and followed on-screen instructions as it took care of pairing itself with the phone.

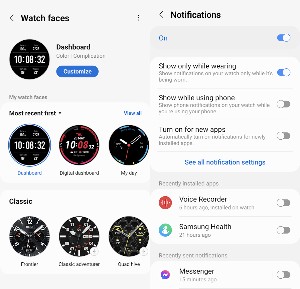

The watch face can be modified to look like an analog watch or a digital watch. I prefer analog displays, but the digital displays allow the easy addition of more information such as the remaining battery charge, the date, my heart rate, and the outdoor temperature. In all there's a choice of more than 20 bits of information. One of my primary reasons for buying a smart watch is its ability to monitor my heart rate. Options are on-demand, every 10 minutes, or continuously. The continuous option is too big a drain on the battery, though, so I chose the 10-minute interval setting.

The watch face can be modified to look like an analog watch or a digital watch. I prefer analog displays, but the digital displays allow the easy addition of more information such as the remaining battery charge, the date, my heart rate, and the outdoor temperature. In all there's a choice of more than 20 bits of information. One of my primary reasons for buying a smart watch is its ability to monitor my heart rate. Options are on-demand, every 10 minutes, or continuously. The continuous option is too big a drain on the battery, though, so I chose the 10-minute interval setting.

The watch's settings can be modified using the watch itself, or the smart phone it's connected to. I found the phone-based settings easier to manipulate, but I've made changes directly on the watch as I've become more familiar with its operations.

The watch's settings can be modified using the watch itself, or the smart phone it's connected to. I found the phone-based settings easier to manipulate, but I've made changes directly on the watch as I've become more familiar with its operations.

The watch has a handy Find My Phone function and the Samsung app on the phone has an equally handy Find My Watch feature. Although I haven't misplaced my phone recently, I have done so in the past. Then I had to have Phyllis call the phone or use Skype to call it.

The number of options, features, and settings on the watch seemed overwhelming. There is a two-page quick start guide that's sufficient to get the watch started, but digging into the feature set requires spending some time with the 81-page manual that's provided as a download from Samsung's website.

Apple introduced their first smart watch in 2015 and a software developer I was working with then was among the first to own one. Seven years later, I have one. But neither of us was near the leading edge.

Microsoft released what's generally considered to be the first true smart watch in 2004. That's right, almost 20 years ago. The Microsoft SPOT (Smart Personal Object Technology) received information such as weather, news, and stock updates, but not via Wi-Fi or Bluetooth. Instead, the SPOT used FM radio.

Even earlier, Seiko offered the Data-2000 starting in 1983. It could store two memos, each no more than 1000 characters. the RC-1000 came out in 1984 and provided a connection to desktop computers.

The watch I'm wearing today can store lot more than 2000 characters. It has 4GB of memory, far more than many desktop computers had in the 1990s. I can also talk to the watch to have it record reminders or other information. There is a keyboard of sorts, but not for my fingers. And talking into the watch makes me feel just a little to much like Dick Tracy.

If you buy a smart watch, set aside some time to read the manual and to experiment with the settings. It seems that the days are gone when it was possible to buy a new piece of hardware or software and use it until there was a problem. I usually download the quick-setup information and manual either before I buy something or while I'm waiting for it to arrive. A quick read-though is usually sufficient for making sense of something initially, but taking the time for in-depth review makes using anything new much more enjoyable in the long term.

The US Federal Bureau of Investigation says 244 investors lost nearly $43 million worth of crypto-currency in the past six month. The scam has been traced back to a fraudulent app.

A warning from the FBI says that cyber criminals purporting to be a legitimate US financial institution defrauded at least 28 victims of approximately $3.7 million during a six month period ending in May. The crypto creeps convinced victims to download an app that used the name and logo of US financial institution that the FBI didn't identify. When some of the victims attempted to withdraw funds using the app, they received an email stating they had to pay taxes on their investments before making withdrawals. After paying the supposed tax, the victims remained unable to withdraw funds.

The FBI says individual investors should follow what appear to be common-sense precautions. Specifically:

The agency's recommendations for financial institutions are also basic common-sense security measures:

The full FBI warning and details of other crypto scams are on the agency's website.

Most routers can transmit signals in the 2.4GHz range and 5GHz range. Some of the newer devices also can communicate in the 60GHz range. Although channel selection is largely automatic in the higher-frequency bands, it's fully manual in the 2.4GHz range.

When you set up a 2.4GHz-band router, it looks like you have a choice of 11 channels. In fact, you should limit the choice to one of three: 1, 6, and 11.

There are simply too many channels. A signal on channel 6 intrudes into channels 4 and 7, and partly into channels 3 and 8. A signal on channel 1 intrudes into channels 2 and 3. And a signal on channel 11 intrudes into channels 9 and 10. That interference is what you want to avoid.

Applications are available for Android devices that show which channels are occupied. The display might show all of the signals in your neighborhood on channels 1, 6, and 11. The intuitive response would be: Those channels are busy, so I should use one of the other channels.

Let's look at a display where there are signals on channels 1 and 2. My signal is on channel 6. A signal centered on channel 1 extends to channels 2 and 3. My signal extends downward from channel 6 through channels 5 and 4. No conflict. But a Wi-Fi channel isn't a hose. A signal may be centered on a given frequency, but it extends well beyond that frequency: A signal centered on channel 2 extends upward to channel to channel 4, where it causes some conflict with signals on channel 6.

So the obvious question is: If cross-channel interference is bad, what about on-channel interference? In an ideal world, every signal would have its own channel. That's not possible, so the Wi-Fi protocols have measures for dealing with signal collisions. The problem is that using one of the channels between the preferred channels generates interference on two primary channels, so there are more collisions to work around.

The only channels that don't overlap another channel are 1, 6, and 11, so those are the only channels that should be used by devices in the 2.4GHz Wi-Fi spectrum. Fortunately, physical separation is sufficient in residential neighborhoods so that both on-channel and off-channel signals are too weak to cause more than minor interference, if they cause any problem at all. The screen shot shows that the interfering signals from a user on channel 2 and another user on channel 10 are down more than 90dBm (decibel-milliwatts), so they pose no problem.

The good news is that this will be less important as people move to the 5GHz band. Wi-Fi routers that operate in the 5GHz band usually have the built-in intelligence to select the best operating channel. Eventually the 5GHz band will fill up, too, but the technology designed for the 60GHz band should eliminate all the cross-channel problems.

This is also a good reason why — when you have a choice — it's always better to use a wired connection.